Senior Fintech Analyst in the South African Reserve Bank's Fintech Unit focused on

open finance and financial inclusion, and co-leading the IFWG's Innovation Accelerator

Cross-border payments sit at the heart of international trade and economic activity. Global cross-border payment flows have experienced a compound annual growth rate of 5% over the last five years growing from about US$128 trillion in 2018 and were estimated to reach US$156 trillion (~ZAR2 538 trillion) in 2022 (which is 151% of global gross domestic product).[1] One of the fast-growing segments in cross-border e-commerce is subscriptions, and the rise of the “subscription economy".[2] In South Africa, it is estimated there are more than 7 million active subscriptions, and the local subscription economy is estimated to be worth US$530 million (~ZAR8.6 billion) – and is anticipated to reach over US$800 million by 2025. These numbers show that the subscription economy in South Africa is on the rise and here to stay. This isn't just a South African phenomenon, as the international subscription economy is expected to reach US$1.5 trillion (ZAR24 trillion) by 2025 from US$650 billion in 2020.

Correspondent banking arrangements currently perform the majority of clearing and settlement functions for cross-border retail payments. However, these correspondence banking networks are characterised by a number of pain-points for customers, including lack of transparency, long settlement periods, high transaction costs, and limited accessibility. While these factors are less likely to be an issue for transactions in liquid currencies (e.g. USD/EUR), they are particularly prevalent in cross-border transactions from emerging markets, as experienced in South Africa, which has one of the most expensive remittance corridors in the world.[3] Such conditions present fertile ground for innovative solutions looking to enhance cross-border payments, leading to new market entrants and technological solutions, prompting questions around the appropriate regulatory fit.

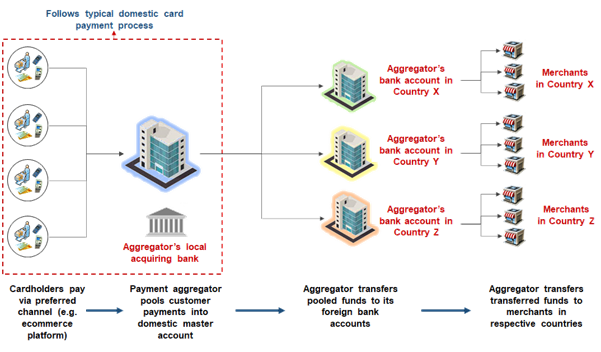

In recent years, payment aggregators have entered the cross-border payment market.[4] At a high level, these payment aggregators seek to provide a master merchant account with banks in South Africa. Through these payment aggregators, local South African entities and individuals do not need to make multiple foreign exchange payments through their banks to perform an electronic funds transfer (EFT) cross-border payment to the foreign merchant's foreign bank account abroad. The payment aggregator holds both an account in South Africa and one in each country in which it operates and makes 'bulk' or 'bundled' transfers between these accounts through the collection of multiple payments in South Africa and disbursement of multiple payments in a foreign country.

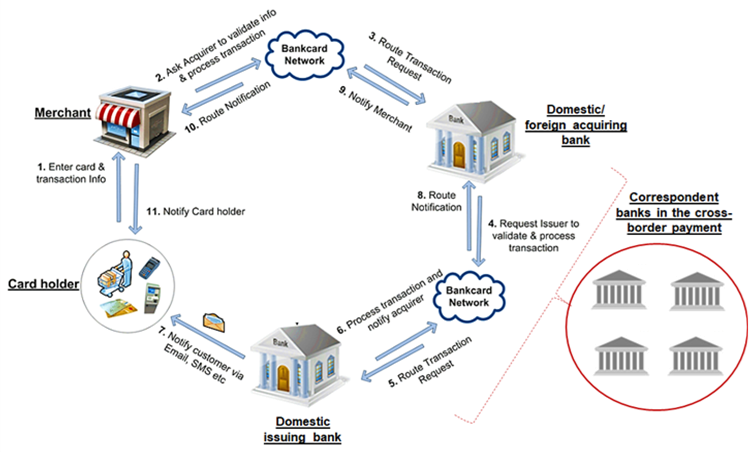

The main purported value proposition of these services is to provide a lower-cost solution compared to consumers making individual payments to the merchant, and provides access to a wider range of payment channels to local consumers through the payment aggregator (e.g., card, EFT, wallets and so on). The aggregator would also take the responsibility of setting up accounts and payment options in the respective jurisdictions and be in charge of negotiating the cross-border payment. The difference between the traditional cross-border payment model and cross-border payment aggregation are shown in figures 1 and 2 below:

Figure 1: Example of a typical domestic and foreign card transaction

Figure 2: Cross-border payment aggregation flow

Innovation challenging the regulatory landscape

This model is novel, and the global regulatory landscape is unclear on how it is treated. For South Africa, cross-border payment aggregation is particularly challenging given the Exchange Control Framework which requires all cross-border transactions to be reported individually to the SARB. This granular reporting is difficult under this model since they effect a bulk payment lacking the data required per transaction to monitor flows for individual entities.

A review of approaches in other jurisdictions revealed a high level of variance as well as uncertainty in terms of the regulatory treatment of this activity. This is best summarised by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) in the results of its 2021 survey on the implementation of FATF Standards which found that:

“Inconsistent supervisory approaches across jurisdictions is [sic] also said to create challenges. The key inconsistency is lack of clear guidance on how financial institutions that provide services to other payment service providers, such as non-banking financial institutions (NBFI), should respond to aggregated payments, bundled at a domestic level, sent cross-border as a single transfer, and then disaggregated in a separate jurisdictions [sic]. In many cases, clarity does not exist on the underlying payment transparency and sanctions obligations for the financial institution facilitating these transfers on behalf of the NBFI."

The FATF paper also adds:

“Conflict between AML/CFT laws and data protection regulations might also affect the transparency of payments as KYC information cannot be shared across jurisdictions. Lack of such sharing might lead to delays in processing and screening. Lack of transparency in the underlying payers/payees when processing aggregated payments from payment service providers, money or value transfer services, or other payments related non-banking financial institutions also adversely affects the transparency of transactions."

Despite the variations, there appears to be some high-level commonalities that can be drawn in terms of frameworks that exist globally. These can be summarised as follows:

1. Enable and regulate as partners of banks: A sample of countries reviewed shows that they have created bank-led, explicit frameworks that enable third-party entities to provide alternative payment channels in efforts to support e-commerce (e.g., India, China, and Egypt).

2. Enable and regulate as independent entities: In some jurisdictions that have introduced open banking and open finance frameworks, payment service providers are able to provide alternative domestic and cross-border payment services by (i) being licensed as payment institutions that are able to initiate payments directly from the bank accounts of customers; or (ii) by being able to provide proprietary payment accounts of their own, such as mobile wallets which are permitted to move funds across the border (e.g. Brazil and Europe).

3. Unclear regulatory environment: In other jurisdictions reviewed, there appears to be less clarity on the environment within which cross-border payment aggregation takes place. Most of these countries have established laws and regulations around foreign exchange business and cross-border funds transfers, which are also bank-led models at the core in the sense that banks remain the primary institutions authorised to effect cross-border transfers (e.g., the United States (US), Canada, United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Australia).

Concluding thoughts

The experiences in other jurisdictions provide useful lessons for South Africa and similar countries as they consider the most appropriate regulatory response. There is clearly no one-size-fits-all solution, and the response will be shaped by each country's own context and nuances. The ultimate route taken will be shaped by various factors including (i) the appetite of policymakers and regulators to amend existing regulations or develop new ones; (ii) whether banks can/should be relied upon as a first-line-of-defence, for example requiring payment aggregators to enter contractual agreements with banks, to reduce the capacity burden on regulators; (iii) the quality and robustness of the payment aggregators' and banks' data, risk and reporting systems and processes; and (iv) the competition dynamics and the need to mitigate anti-competitive behaviours. This will also require engagement with various stakeholders, both internal and external, to ensure that the outcome is appropriate for the domestic environment.

[1] Ernst & Young, 2021, How new entrants are redefining cross-border payments.

[2] Subscription economy is a term used to describe the new economic landscape where customers are showing a preference for lower cost, subscription-based products and services over the traditional pay-per-product model.

[3] World Bank, 2021, Defying Predictions, Remittance Flows Remain Strong During COVID-19 Crisis.

[4] Ernst & Young, 2021, How new entrants are redefining cross-border payments

Disclaimer: As the IFWG we are enthusiastic to include diverse voices through our media content. The opinions of participants do not necessarily represent the views of the IFWG and their respective organisations.

Disclaimer: As the IFWG we are enthusiastic to include diverse voices through our media content. The opinions of participants do not necessarily represent the views of the IFWG and their respective organisations.