In defi-ance of centralised finance

By Gerhard van Deventer and Herco Steyn | 12 December 2021

GERHARD VAN DEVENTER

Senior Fintech Analyst in the South African Reserve Bank’s Fintech Unit focussed on financial market innovation (including being the product owner for Project Khokha) and co-leading the IFWG’s Regulatory Sandbox. |

HERCO STEYN

Senior Fintech Analyst in the South African Reserve Bank’s Fintech Unit where he focuses on crypto assets, stablecoins and emerging forms of private ‘money’.

|

In DeFi-ance of centralisation?

According to Harvey and colleagues (2021: 1) decentralised finance (DeFi) “poses a challenge to the current system and offers a number of potential solutions to the problems inherent in the traditional financial infrastructure” and fintech initiatives which “embrace the current banking infrastructure are likely to be fleeting” while those utilising decentralised methods “have the best chance to define the future of finance”. In this blog, we expand on the meaning of DeFi, examine some use cases, benefits and risks of DeFi and finally consider the potential implications.

What is DeFi?

According to (Schär, 2021) DeFi is an alternate financial infrastructure built on distributed ledger technology (DLT), primarily Ethereum (as the largest smart contract platform), utilising smart contract enabled protocols and decentralised applications (DApps) for a more “open, interoperable, and transparent” replication of financial services. DeFi does not rely on intermediaries and centralised institutions. Agreements in DeFi are enforced by code; and DeFi architecture allows transactions to be executed in a secure and verifiable manner creating an immutable and transparent financial system (Schär, 2021). Smart contracts are the backend components of DApps which enable peer-to-peer interaction (Harvey et al, 2021: 12). The DeFi Pulse[1] website listed lending; decentralised exchanges (DEXs); derivatives; payments and assets as the main DeFi categories at the time of writing. The website offers the simple definition that DeFi is financial software built on DLT which may be put together like ‘Money Legos’. The size of the market is measured in total value locked (TVL) which is the value of funds locked in smart contracts for use in DeFi applications.

DeFi components

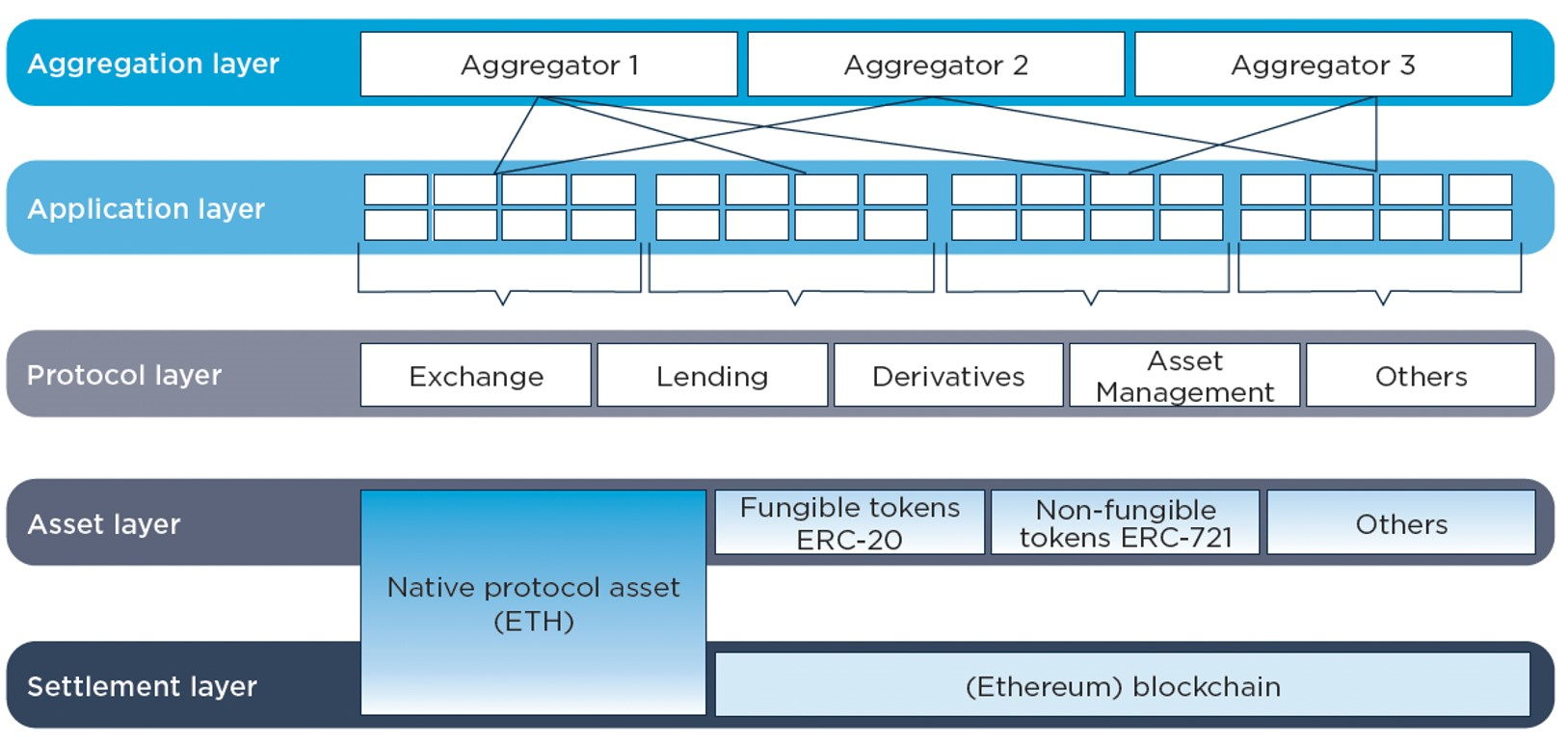

Schär (2021) sets out a multi-layered DeFi architecture (depicted in Figure 1 below) creating an open, hierarchical and composable infrastructure enabling building with the ‘Money Legos’. The foundational (first) layer is the settlement layer and its native DLT protocol asset (e.g., BTC or ETH) enabling recording ownership information according to its ruleset. The asset layer consists of the native protocol asset and other assets (tokens) issued on the DLT. The protocol layer entails the standards applied to a particular use case which are typically implemented as a set of smart contracts which are accessible by other users. The application layer is the fourth layer and consists of user-oriented applications which connect individuals to specific protocols (the layer 3 smart contracts) and is extended in the aggregation layer which create user-centric platforms connecting several applications and platforms.

Figure 1: Schär’s DeFi Stack

(Schär, 2021)

DeFi use cases

In this section we will briefly consider five DeFi categories (based on the functionality of the DApps) with some sample use cases (noting that some span multiple categories, and secondly with the blog being drafted at a specific point in time and by the time you read this some of the examples may no longer be pertinent).

DeFi offers decentralised

lending platforms which offer two types of lending protocols (Schär, 2021):

Collateralised loans have a minimum threshold and should the collateralisation drop below the threshold, the smart contract liquidates and closes the position using an external ‘keeper’ who is incentivised through a reward.

Flash loans are uncollateralised instantaneous loans paid back within the same transaction enforced by the smart contract and may be used in arbitrage opportunities or to refinance loans (Harvey et al, 2021: 32-33).

Collateralised debt positions can be created by issuing new tokens, which are backed by collateral e.g., MakerDAO (Schär, 2021). Aave is a lending market protocol with the ability to create new markets consisting of token pools with its own supply and borrow rates, but currently has two main markets, i.e., one for conventional ERC-20 tokens and one for Uniswap LP tokens. Aave also supports flash loans (Harvey et al, 2021: 50).

Uniswap is an example of a

DEX protocol on Ethereum and particularly an automated market maker using liquidity pools to enable token exchange. A global market exists for each token’s borrowing and lending pools. Any token holder can contribute her tokens to the liquidity pool and earn interest on her token holdings. Uniswap also offers flash swaps (similar to flash loans), allowing the user to borrow an asset for a single arbitrage opportunity completed in a single Ethereum transaction (Harvey et al, 2021: 53-58; Voshmgir 2020: 267).

Decentralised

derivative tokens derive their value from the outcomes of an event, the performance of an underlying asset, or another variable and may require an oracle to track relevant external (to the protocol) developments. A distinction could be made between asset-based (price depends on performance of underlying) and event-based (price depends on observation of other variables) derivative tokens (Schär, 2021). Synthetix issues tokens backed by collateral and with their price pegged to an underlying price feed called Synths (Harvey et al, 2021: 67). The total debt pool of all participants will decrease or increase based on the aggregate price of all outstanding synthetic assets (Schär, 2021).

From a DeFi

payments perspective Flexa[2] claims to be the “fastest, most fraud-proof payments network in the world”. It guarantees settlement, flexible integration and to support payment in various currencies. Tornado Cash[3] is a fully decentralised protocol providing private payments on Ethereum through breaking the on-chain link between source and destination addresses.

Looking at

asset management, on-chain funds are mainly used to allow users to diversify their portfolios and invest in a basket of crypto assets utilising a variety of strategies while providing custody services by locking up the assets in the smart contracts. The smart contracts can also be used to enforce adherence to predefined strategies and protect investor interest. Protocols tend to be restricted to ERC-20 tokens and Ether, while they heavily rely on oracles and third-party protocols. The Set Protocol combines various Ethereum tokens into composite tokens (Sets) which could be compared to exchange traded funds and enables anyone to create a new investment fund. The protocol is primarily designed for semi-automated strategies with predetermined portfolio rebalancing triggers, although it can also be used for active management (Harvey et al, 2021: 70; Schär, 2021).

Why DeFi? (Benefits and risks)

In this section we consider some of the proposed benefits and potential risks of DeFi. Opportunities highlighted by Schär (2021) include that the composability of DeFi’s Lego Blocks enables innovation and that it may increase the accessibility, transparency and efficiency of financial infrastructure. Accessibility here refers to access not being restricted (and does not address digital exclusion and financial education) although regulatory restrictions could be implemented through smart contracts. Harvey and colleagues (2021: 5) list five problems which DeFi seeks to address, namely: inefficiency; limited access; opacity (lack of transparency); centralised control; and lack of interoperability. In talking about centralised control, they seem to refer to two aspects which is worth clearly splitting out, namely making a distinction between the centralisation of control within an organisation and the concentration of market power (specifically market structures of oligopoly and monopoly). This is an important distinction to make since even a market of decentralised organisations could be oligopolistic and its design would have to consider competition and other factors which are challenges in the current financial system. Harvey and colleagues (2021: 5-6) do talk about the many layers of centralisation and the tendency of concentration around bigtech platforms.

Some risks unique to, or impacted by, DeFi are (Harvey et al, 2021: 3-4; Schär, 2021):

Custodial risk – there are risks involved in self, partial and third-party custody;

Dependence on other protocols – interconnectivity between protocols may increase complexity and systemic risk should certain protocols fail or struggle;

DEX risk – there has been an explosion in the use of DEXs, with its inherent use of leverage, trading and being exposed to volatile assets – which may be exacerbated through automation and some of the other DeFi risks;

Governance risk – DeFi protocols and their governance systems are set up in different ways, and risk may emanate from the protocol itself[4] or from potential subsequent human-based governance structure set up to manage the protocol risk e.g., a takeover of the structure;

Operational, including information security, risk – for instance surrounding the management of admin keys and there are also concerns surrounding privacy and responsibility for illicit transactions);

Oracle risk – stems from dependence on external sources of data;

Regulatory risk – considerations include regulatory uncertainty, allowing responsible innovation with reasonable regulation and the feasibility of regulating a decentralised infrastructure;

Scaling risk – there are limits on the number of transactions a DLT may process per second; and

Smart contract risk – this entails poorly engineered code which allows for unintended consequences, including exploitation by malicious users or incentivising poor behaviour.

Final reflections

Now that we’ve DeFined DeFi and looked at some of the benefits we will briefly reflect on some DeFi governance design considerations to help overcome the multiple challenges highlighted earlier. It could be argued that currently DeFi is built more for developers than the average user. For DeFi to achieve mainstream credibility, strong consideration needs to be given to its ‘social governance’ and the ‘algorithmic administration of governance’ (Voshmgir, 2020: 158, 214). It is important to recognise that the development of these public infrastructures is currently limited to a small group of people, however designing such systems should be viewed as similar to designing national economies. In this way, the design of DeFi protocols is more akin to public policy design and should therefore include technical engineering, legal engineering, economic engineering and ethical engineering (Voshmgir, 2020: 166, 375, 388).

To quote the Danish proverb – it’s difficult to make predictions – particularly about the future, and it is similarly difficult to predict DeFi’s future role in finance. Traditionally banks play a role in intermediating between savers and lenders, in transforming needs and wants in terms of size (big vs. small amounts); maturity (short vs. long-term); and risk (averse vs. risk-taking). DeFi protocols do have value, but the jury is still out on whether it could effectively perform all these roles and whether users are ready, and sophisticated enough, to put their trust and (all, or much of, their) money in DeFi offerings? Could DeFi along with artificial intelligence potentially signal a return, at least in part, to a tokenised barter economy as global trading platforms resolve the coincidence of wants problem (Voshmgir, 2020: 216)? There remain many challenges for DeFi to overcome. Effective governance arrangements are a core building block, otherwise the ‘Money Legos’ could build a muddle comparable to the complex system the resulted in the global financial crisis. While current DeFi protocols do have value in the form of more efficient and more inclusive financial services, regulators should remain vigilant to the build-up of risks in a largely unregulated space and potential spill-overs to traditional financial markets. Having started with a quote from Harvey and colleagues we will close with another, without “proper risk mitigation, DeFi will remain an exploratory technology, restricting its use, adoption, and appeal” (2021: 72).

Notes

[1]https://defipulse.com/ [Accessed on 10 June 2021]

[2]https://flexa.network/ [Accessed on 12 June 2021]

[3] https://tornado.cash/ [Accessed on 12 June 2021]

[4] A protocol in essence creates a governance system built into the code seeking to incentivise behaviour beneficial to the system (for instance rewarding transaction verification with tokens) – these governance protocols may however have certain biases in them and have unintended consequences which may be detrimental to the DeFi protocol and/or its users.

Bibliography

Harvey, CR, Ramachandran, A, & Santoro, J. (2021) DeFi and the future of Finance. 05 April 2021 version. Available from:

https://ssrn.com/abstract=3711777 [Accessed on 3 May 2021]

Schär, F. (2021) Decentralized Finance: On Blockchain- and Smart Contract-Based Financial Markets. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis – Economic Research. 5 February 2021. Available from:

https://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/review/2021/02/05/decentralized-finance-on-blockchain-and-smart-contract-based-financial-markets [Accessed on 3 May 2021]

Voshmgir, S (2020) Token economy – How the web3 reinvents the internet. 2nd edition. Token Kitchen, Berlin.

...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

SHARE THIS BLOG

Disclaimer: As the IFWG we are enthusiastic to include diverse voices through our media content. The opinions of participants do not necessarily represent the views of the IFWG and their respective organisations.

Disclaimer: As the IFWG we are enthusiastic to include diverse voices through our media content. The opinions of participants do not necessarily represent the views of the IFWG and their respective organisations.